This continuing professional development (CPD) supplement focuses on the regulatory framework available to drug developers for expediting their products’ development and review processes in the EU and US. These mechanisms are relevant for products which address an unmet medical need in the treatment of a serious and/or life-threatening condition.

Patients with serious or life-threatening illnesses could benefit from drugs that are currently in development. Regulatory designations and pathways are designed to help accelerate the development and/or the review period for medicinal products designed to address unmet medical needs for patients that suffer from seriously debilitating or life-threatening diseases.

Europe

In the EU there are three pathways available to potentially expedite time to market – accelerated assessment,[1] conditional marketing authorisation[2] and authorisation under exceptional circumstances[3] (see Table 1). Accelerated assessment and conditional marketing authorisation can reduce time to market via shortening the marketing authorisation application (MAA) assessment time and affording approval based on a preliminary assessment of benefit–risk, respectively. Both procedures lead to eventual registration based on a full data package. In contrast, authorisation under exceptional circumstances can expedite time to market by allowing evaluation of benefit–risk based on a less comprehensive data package (in specific circumstances). The priority medicines (PRIME) scheme is available to expedite the development of certain therapies.[4]

| EU accelerated MA | EU conditional MA | EU exceptional circumstances MA |

|---|---|---|

| Demonstrate major public health interest particularly through therapeutic innovation | Demonstrate positive benefit–risk balance, based on scientific data, pending confirmation | Comprehensive data cannot be provided (specific reasons foreseen in the legislation) |

| The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use can revert to standard centralised procedure (CP) timelines at any time during MAA evaluation, if criteria no longer met | Authorisation valid for one year, on a renewable basis | Reviewed annually to reassess the benefit–risk balance, in an annual re-assessment procedure |

| Standard CP marketing authorisation granted | Once the pending studies are provided, it can become a ”standard” marketing authorisation | Will normally not lead to the completion of a full dossier and become a “standard” marketing authorisation |

EU – accelerated assessment

Article 14(9) of Regulation 726/2004 defines the legal basis for accelerated assessment.[5] The procedure reduces the timeframe for the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) to review an MAA. Marketing applications may be eligible for accelerated assessment if the CHMP decides that the product is of major interest for public health and therapeutic innovation.

A developer granted accelerated assessment can benefit from a reduction in assessment time from the standard 210 to 150 days. Both times are not inclusive of clock-stops, which are periods when the evaluation of a medicine is officially stopped while the applicant prepares responses to questions. The clock resumes when the applicant has sent its responses. Prospective applicants are encouraged to discuss the potential for review under accelerated assessment at an MAA pre-submission meeting six to seven months ahead of MAA submission, or if relevant during a PRIME meeting. A request for assessment of an MAA under accelerated assessment with the applicant’s justifications should be made before MAA submission (typically two to three months). This should also include information concerning good manufacturing practice (GMP) and good clinical practice (GCP) aspects so that routine GCP and pre-approval GMP inspections can be integrated into the accelerated assessment procedure.

EU – conditional marketing authorisation

Regulation 507/2006 amending 726/2004 describes the scope and legal basis for conditional marketing authorisation (CMA).[6] A CMA approval may be granted for a medicinal product fulfilling an unmet medical need when the benefits to public health of immediate availability outweigh the risk inherent in the fact that additional data are still required. CMAs are based on less complete clinical data than is normally the case and subject to specific obligations. However, the dossier at the time of submission must still be mature and robust. A CMA can be discussed during scientific advice/protocol assistance, where late-phase clinical development plans take into account CMA strategy and then proactively requested by the applicant six or seven months ahead of MAA submission, or at the time of MAA submission.

However, it can be proposed by the CHMP (after having consulted with the applicant) during the assessment of the application. CMAs are valid for one year, to be renewed annually based on review of specific obligations and reconfirmation of the benefit–risk balance. The CHMP will assess the benefit–risk balance as part of the renewal application and determine whether the specific obligations or their timeframes need to be retained or modified and whether the MA should be maintained, varied, suspended or revoked. Ultimately, the MAH must provide more data post-licensing in a pre-agreed timeframe as part of these specific obligations and then converts to a full MA. Non-compliance with these obligations may lead to regulatory action up to and including MA revocation.

EU – exceptional circumstances

Article 14(8) of Regulation 726/2004 defines the legal basis for authorisation under exceptional circumstances (AEC).[7] AEC can be granted when there is no reasonable expectation that a complete data package will be available because:

- The indications for which the product in question is intended are encountered so rarely that the applicant cannot reasonably be expected to provide comprehensive evidence, or

- In the present state of scientific knowledge, comprehensive information cannot be provided, or

- It would be contrary to generally accepted principles of medical ethics to collect such information.

The amount of data typically supplied for an AEC can be more limited when compared with a CMA. Sponsors should seek scientific advice from the EMA as early as possible in development on the justification for an AEC. Sponsors should further specify in their letter of intent the proposal to pursue an AEC. Ultimately the rapporteur, co-rapporteur and CHMP will determine suitability based on the benefit–risk balance and the availability of data. AEC approvals are not common, are valid for five years, and are contingent on an annual reassessment procedure. This procedure re-evaluates the benefit–risk balance and the completion of specific obligations placed on the marketing authorisation holder.

EU – priority medicines (PRIME)

The PRIME scheme, introduced in 2016 by the EMA[8], is a designation typically granted in early clinical development stages for medicinal products that are of major interest from the point of view of public health and therapeutic innovation. The PRIME designation affords enhanced interaction and early dialogue with regulators, with the objectives of collaborative optimisation of development plans and increasing efficiencies, accelerating time to market for products being developed in areas of unmet medical need.

Receiving PRIME designation bestows several benefits, including multiple scientific advice meetings with the EMA, as well as parallel advice with EMA and health technology assessment (HTA) bodies. Once a candidate medicine has been selected for PRIME, the agency will appoint a rapporteur to provide continuous support and help to build knowledge ahead of an MAA. The rapporteur will also organise a kick-off meeting with the CHMP/ Committee for Advanced Therapies (CAT) rapporteur and a multidisciplinary group of experts, so that they provide guidance on the overall development plan and regulatory strategy. PRIME designation holders may submit an MAA for full approval, conditional approval, or through exceptional circumstances approval, and may also request an accelerated assessment. The EMA website provides details on the process and on how to apply for PRIME designation.[9]

United States

In May 2014 the US FDA introduced the “Guidance for industry: expedited programs for serious conditions – drugs and biologics”[10],which provides information about four distinct expedited programmes that the FDA offers: fast track, breakthrough therapy, accelerated approval, and priority review. The Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research issued a guidance in February 2019 titled “Expedited programs for regenerative medicine therapies for serious conditions”, which discusses clinical development considerations for regenerative medicine therapies, including regenerative medicine advanced therapy designation (RMAT). [11]These designations are open to all small molecule drugs and biologics except for RMAT, which was specifically created for CBER-regulated regenerative medicines intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious condition.

A product may receive more than one designation, although an application should be submitted for each. Complementary to these formal mechanisms is the FDA’s Critical Path initiative, which aims to modernise the scientific process from discovery through to final medicinal product.[12]

US – priority review

When a marketing application is filed, the FDA makes a determination of standard versus priority review and notifies the applicant of its decision within 60 days of the submission date. The benefit of priority review designation is that it reduces new drug application (NDA)/biologics license application (BLA) review timelines from 10 to 6 months after the 60-day filing date. Priority review designation is available for medicines that offer significant improvements in the safety or effectiveness of the treatment, diagnosis or prevention of serious conditions. The FDA determines if a proposed drug would be a significant improvement at the time of filing for NDAs, BLAs, and efficacy supplements.

Examples of “significant improvement” include improved diagnosis, prevention or treatment of a condition; elimination or substantial reduction of a treatment-limiting adverse drug reaction; enhancement of patient compliance which would be expected to result in an improvement in outcomes or evidence of improved clinical safety and/or effectiveness in a defined subpopulation of a wider condition.[13]Products granted fast track or breakthrough therapy designation may qualify for priority review status.

US – accelerated approval

The Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) was amended in 1992 to allow the FDA to improve access to drugs intended for serious conditions that fill an unmet medical need on the basis the drug has an effect on a surrogate endpoint or an intermediate clinical endpoint.[10] Surrogate endpoint is defined as a laboratory measurement, radiographic image, physical sign or other measure that is thought to predict clinical benefit but is not a measure of direct patient benefit. Intermediate clinical endpoint is defined as a measure of a therapeutic effect that is considered reasonably likely to predict the clinical benefit of a drug, such as an effect on irreversible morbidity and mortality (IMM).

The use of surrogate or intermediate endpoints have the potential to save time to approval and have been used extensively in oncology, where approval based on evidence of tumour shrinkage or progression-free survival are considered reasonably likely to predict real clinical benefit (ie, overall survival). Following accelerated approval, the sponsor still must verify the anticipated effect on irreversible morbidity or mortality and/or other clinical benefit in order to achieve full approval. Approval is also possible with provision of flexibility of the standards of required safety data if preliminary analysis of Phase II data appears promising.[14] Commitments may also be necessary to conduct post-marketing (Phase IV) studies to include study of different doses or administrations, sub-populations or longer drug duration. As with the EU, the FDA can withdraw an accelerated approval if the US studies do not confirm preliminary results. Post-marketing studies should therefore be underway at the time of the accelerated approval submission. The sponsor needs to show diligence in completing studies in a timely manner and be prepared to provide status updates.

US – fast track

Also introduced in 1992, fast track is designed to facilitate the development and expedite the review of drugs intended to treat serious conditions as well as address an unmet medical need.[10] Determinations of whether or not a condition is serious is up to the judgement of US regulators, where the FDA takes into consideration the survival, day-to-day functioning, and progression of the disease if left untreated.[15] Fast track designation can be based on nonclinical or clinical data and may be available with relevant, nonclinical data prior to clinical benefit signal in human clinical studies. The FDA received 2,287 requests for fast track designation from fiscal year 1998 through 2019. Looking at data from the past five years, the majority of applications are made at Phase II (44%).[16] For the fiscal years of 2012 and 2018, 70% of the fast track applications were granted, 25% were denied, and 5% were unable to be granted or denied (eg, the application was withdrawn).[17] Fast track allows access to the FDA’s rolling review process, where it allows submission of the NDA or BLA in stages, more frequent interactions with the FDA and, if the relevant criteria are met, may make an eventual BLA or NDA eligible for priority review.

US – breakthrough therapy designation

Breakthrough therapy designation (BTD) was introduced in 2012 to support development of drugs for the treatment of prevention of serious or lifethreatening diseases, or condition when preliminary clinical evidence indicates the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over existing therapies on one or more clinically significant endpoints, such as substantial treatment effects observed early in clinical development.[10] A drug that receives breakthrough therapy designation is eligible for all fast track designation features but also receives intensive guidance on an efficient drug development programme, beginning as early as Phase I, and an organisational commitment involving senior managers at the FDA. As with fast track, BTD also gives developers access to FDA’s rolling review process.

US – RMAT designation

In 2017, the FDA introduced the new RMAT designation in the 21st Century Cures Act, recognising the potential of advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) and the need for efficient regulatory tools to accelerate their development. RMAT is unique in that it applies only to regenerative medicine therapies, defined as a cell therapy, gene therapy, tissue-engineered product, human cell and tissue product, or any combination of these therapies. To qualify for RMAT, a product must be intended to treat or cure serious, life-threatening conditions where preliminary clinical evidence indicates the drug has the potential to address unmet medical needs. Unlike BTD, RMAT does not require evidence to demonstrate substantial improvement over other available therapies. The benefits of RMAT include all of those conferred by fast track designation and BTD with increased interactions with FDA reviewers as well as eligibility for priority review. In addition, “flexibility” is theoretically available in the number of clinical sites used and the possibility to use patient registry data and other sources of real-world evidence for post-approval studies.[18] The Office of Tissues and Advanced Therapies (OTAT) reviews and provides a response to RMAT designation requests within 60 calendar days.

Comparison/limitations of EU and US pathways

Table 2 (adaptation from Nagai S, Int J Mol Sci 2019;20[15]:3801[19]) provides a comparison of the features and requirements, where possible, between analogous EU and US regulatory procedures and mechanisms for accelerating drug development and approval. Of note, the EU accelerated assessment is not comparable to US accelerated approval, despite the connotations with the naming terminology.

A 2020 publication which conducted a retrospective analysis of EMA and FDA decisions from 2014 to 2016 found high concordance (91%) in the agencies’ initial decisions on marketing approval, with this increasing to 98% following review of resubmitted or re-examined applications.[20] Previous FDA evaluation of regulatory outcomes between January 2006 and October 2008 found that the EMA and the FDA had similar rates of approval (67% and 64%, respectively) and 64% of applications were approved by both agencies. However, another study of new applications between 1995 and 2007 suggested that, despite the similar rates of overall approval, many of the applications approved by the FDA were not approved by the EMA, and vice versa.

For the 98 applications approved (Table 3), the FDA and the EMA diverged 15 of these in the type of marketing authorisation (one agency granted standard approval, the other did not), whereas 76% (74/98) were approved by both agencies as standard approval. 19% (19/98) of the approved applications received accelerated approval from the FDA, and the EMA granted conditional marketing approval to 11% (11/98). These approval mechanisms were employed by both agencies for the same products for only 9% (9/98) of approvals. Three EMA approvals granted under “exceptional circumstances” received FDA standard approvals.

Unsurprisingly, oncology and haematology therapeutic areas were granted more approvals under expedited pathways. However, the FDA more commonly granted accelerated approval (12/25 in oncology and 5/8 in haematology) than the EMA granted CMA or an MA under exceptional circumstances (7/25 in oncology and 2/8 in haematology).

| EU | US | |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Accelerated assessment | Priority review |

| Features | Target total review time: 150 days (excluding the time that applicants require for responses to the CHMP’s questions) (standard assessment: 210 days) | Target total review time for original NDA/BLA: 8 months (6 months plus 60 filing days) (Standard review: 12 months (10 months plus 60 filing days)). Target total review time for efficacy supplement: 6 months (Standard review: 10 months) |

| Requirements |

1. Important in terms of public health and innovation 2. Strong evidence 3. Fulfils an unmet medical need |

1. Treatment for a serious disease and would significantly improve safety or effectiveness, or 2. Any supplement that proposes a labelling change pursuant to a report on a paediatric study, or 3. An application for a drug that has been designated as a qualified infectious disease product, or 4. Any application or supplement for a drug submitted with a priority review voucher |

| Mechanism | Conditional MA | Accelerated approval |

| Features |

1. Applicable to applications of initial MA only, with efficacy extensions beyond the scope 2. Active for one year only with an annual renewal of the approval continuing until the EMA converts the conditional approval to standard MA |

Expedited approval based on an effect on a surrogate endpoint or an intermediate clinical endpoint that is reasonably likely to predict a drug’s clinical benefit. |

| Requirements |

1. Fulfilling an unmet medical need 2. Pertaining to life-threatening, serious, or emergency diseases, or orphan products 3. The company being able to provide clinical data comprehensively 4. A positive benefit–risk balance |

1. Drugs treating serious conditions 2. Demonstrating a meaningful advantage over other available drugs based on a surrogate endpoint that is reasonably likely to infer a clinical benefit 3. Postmarketing confirmatory studies are required to demonstrate benefits |

| Mechanism | MA under exceptional circumstances | No analogous US procedure |

| Features | Applicants do not need to submit comprehensive data in order to convert to normal MA | Not applicable |

| Requirements |

1. Applicants are not able to provide clinical data comprehensively because of the rarity of the disease for example 2. Applicable to life-threatening or serious diseases |

Not applicable |

| Mechanism | Priority medicines (PRIME) | Breakthrough therapy designation or regenerative medicine advanced therapy (RMAT) designation |

| Features |

1. The appointment of a rapporteur from the CHMP or CAT to provide continuous support 2. The organisation of a kick-off meeting with the rapporteur and experts to provide guidance on development plan and regulatory strategy 3. The assignment of a dedicated point of contact 4. The provision of scientific advice at key development milestones 5. Potential for accelerated assessment |

1. Rolling review 2. FDA’s intensive guidance on a drug development programme 3. Organisational commitment involving senior management 4. Priority review if applicable, with the FDA finishing its review at least one month earlier than the PDUFA VI goal date 5. Early interactions with the FDA to help with addressing potential ways to support accelerated approval and satisfy post-approval requirements (only for RMAT) |

| Requirements |

1. Products under development are not approved in the EU and for which a sponsor intends to apply for an initial MAA through the centralised procedure via the EMA 2. It targets conditions with an unmet medical need (no satisfactory method of diagnosis, prevention, or treatment, or is of major therapeutic advantage to patients) (identical to the accelerated assessment criteria) 3. It demonstrates the potential to address the unmet medical need in terms of maintaining and improving health and is of major public health interest from the viewpoint of therapeutic innovation (identical to the accelerated assessment criteria) |

Breakthrough therapy designation: 1. It is intended to treat a serious condition 2. Preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the drug demonstrates substantial improvements on a clinically significant endpoint over available therapies RMAT: 1. The drug is a regenerative medicine therapy, which is defined as a cell therapy, therapeutic tissue-engineered product, human cell and tissue product, or any combination product using such therapies or products 2. It is intended to treat, modify, reverse, or cure a serious condition 3. The preliminary clinical evidence indicates that the regenerative medicine therapy has the potential to address unmet medical needs for the condition |

TABLE 3 Comparison of EMA and FDA Decisions for new drug marketing applications 2014–2016

| EU exceptional circumstances MA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard (84) | Conditional (11) | Exceptional (3) | ||

| FDA marketing approval type (n=98) | Standard approval (79) | 74 (76%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) |

| Accelerated approval (19) | 10 (10%) | 9 (9%) | N/A | |

Agency differences in the type of marketing approval were attributable to differing conclusions about efficacy (47%, 7/15) and differences in the submitted clinical data (47%, 7/15). In most cases (5/7 applications), the agencies had dissimilar clinical data because one agency reviewed additional trials (rather than updated data from an initially submitted trial). Commonly FDA submissions were made significantly ahead of the EMA filing, and most FDA second cycle approvals (ie, approvals after resubmission) were based on submission by the sponsor of the same additional data that EMA had received during its initial review either from the start or following request after clock-stops.

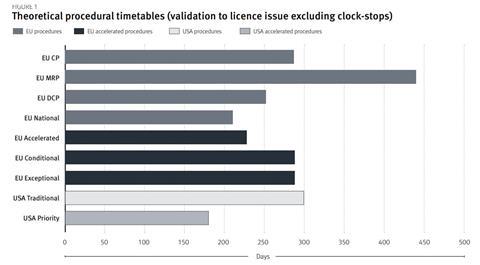

Figure 1 summarises the timelines of EU and US procedural options, however, it does not reflect the expedited time to market through more rapid development (exceptional and conditional approvals) and rolling assessment. In a 2008 study of 71 products approved in the US and EU, 73% were approved in the US first, with a lead time of 11.8 months[21]. The US approval times demonstrated greater divergence between accelerated and traditional mechanisms, however, they were subject to more variability.

It is important to realise and assess the limitations of such accelerated procedures and attribute an associated risk, for example, of not fulfilling specific obligations, or introducing blinded study bias with CMA grant while ongoing or recruiting. The EMA published a 10-year report on the CMA[22] and reported that, of the 30 medicines to receive a CMA, none had to be revoked or suspended and four were withdrawn for commercial reasons. Subsequently, in 2019, one conditional MA was revoked as the study failed to meet the primary endpoint (see case study for further details).

In the US, the use of accelerated assessment programmes has increased over its 25-year history, particularly for oncology drug approvals[23]. In a recent analysis, 56% of all drugs receiving accelerated approvals have been converted to full approval. However, 7% of all accelerated approvals have been withdrawn. Of these 14 withdrawals, 10 applications were withdrawn, and four indications were removed but the drug remained on the market. For the majority of accelerated approval withdrawals, confirmatory studies were either not done or did not show clinical benefit and the average time on the market before withdrawal was 8.6 years (ranging from 3.4 to 11.7 years).[24]

Various regulatory procedures and strategies can help to accelerate the development or the review period for new medicinal products which address unmet medical needs in both the EU and the US. However, companies should be aware of the nuances between the different regional regulatory mechanisms, and of the additional complexities and challenges this can have for global product development.

[1] EMA. Accelerated assessment. Available at: https://www.ema. europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation/ accelerated-assessment (accessed 19 July 2020).

[2] 2. EMA. Conditional marketing authorisation. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketingauthorisation/conditional-marketing-authorisation (accessed 19 July 2020).

[3] EMA. Is my medicinal product eligible for approval under exceptional circumstances? Available at: https://www.ema. europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation/ pre-authorisation-guidance#1.-types-of-applications-andapplicants-section (accessed 19 July 2020).

[4] EMA PRIME. Priority medicines. Available at: https://www.ema. europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/research-development/primepriority-medicines (accessed 19 July 2020).

[5] EMA. Guideline on the scientific application and the practical arrangements necessary to implement the procedure for accelerated assessment pursuant to Article 14(9) of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. 2016. Available at: https://www.ema. europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/guidelinescientific-application-practical-arrangements-necessaryimplement-procedure-accelerated/2004_en.pdf (accessed 19 July 2020).

[6] EMA. Guideline on the scientific application and the practical arrangements necessary to implement Commission Regulation (EC) No 507/2006 on the conditional marketing authorisation for medicinal products for human use falling within the scope of Regulation (EC) No 726/2004. 2016. Available at: https:// www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/ guideline-scientific-application-practical-arrangementsnecessary-implement-commission-regulation-ec/2006- conditional-marketing-authorisation-medicinal-productshuman-use-falling_en.pdf (accessed 19 July 2020).

[7] EMA. EMEA/357981/2005. Guideline on procedures for the granting of a marketing authorisation under exceptional circumstances, pursuant to article 14 (8) of regulation (ec) no 726/2004. 15 December 2005. https://www.ema.europa. eu/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/guidelineprocedures-granting-marketing-authorisation-under-exceptionalcircumstances-pursuant/2004_en.pdf (accessed 19 July 2020).

[8] EMA. EMA/CHMP/57760/2015, Rev. 1 Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use. 07 May 2018. https://www.ema. europa.eu/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/ enhanced-early-dialogue-facilitate-accelerated-assessmentpriority-medicines-prime_en.pdf (accessed 19 July 2020).

[9] EMA. Enhanced early dialogue to facilitate accelerated assessment of PRIority Medicines (PRIME) ema.eurpa.eu. European Medicines Agency: PRIME: Priority Medicines. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/ regulatory-procedural-guideline/enhanced-early-dialoguefacilitate-accelerated-assessment-priority-medicines-prime_ en.pdf (accessed 19 July 2020).

[10] FDA. Guidance for industry. Expedited programs for serious conditions – drugs and biologics. May 2014. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fdaguidance-documents/expedited-programs-serious-conditionsdrugs-and-biologics (accessed 22 June 2020).

[11] FDA. Expedited programs for regenerative medicine therapies for serious conditions, guidance for industry. February 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/media/120267/download (accessed 22 June 2020).

[12] FDA. FDA’s critical path initiative. Available at: https://www.fda. gov/science-research/science-and-research-special-topics/ critical-path-initiative (accessed 22 June 2020).

[13] FDA. Priority review. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/patients/ fast-track-breakthrough-therapy-accelerated-approval-priorityreview/priority-review (accessed 26 June 2020).

[14] Subpart e-drugs intended to treat life-threatening and severelydebilitating illnesses. Code of Federal Regulations; Title 21, Volume 5: Sec. 312.80 Purpose. Revised April 1, 2007. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/ CFRSearch.cfm?fr=312.80 (accessed 22 June 2020).

[15] Cox EM, Edmund AV, Kratz E et al. Regulatory Affairs 101: introduction to expedited regulatory pathways. Clin Transl Sci 2020;13:451–461.

[16] Early data supports most fast track requests – five years of fast track designation announcements. Informa Pharma Intelligence, 2020.

[17] FDA. CDER fast track designation requests received, fiscal year 1998 – fiscal year 2018. Available at: www.fda.gov/ media/97830/download (accessed 17 August 2020).

[18] Barlas S. The 21st Century Cures Act: FDA implementation one year later: some action, some results, some questions. P&T 2018;43(3):149–179. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/pmc/articles/PMC5821241/ (accessed 17 August 2020).

[19] Nagai S. Flexible and expedited regulatory review processes for innovative medicines and regenerative medical products in the US, the EU, and Japan. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3801.

[20] Kashoki M, Hanaizi Z, Yordanova S et al. A comparison of EMA and FDA decisions for new drug marketing applications 2014–2016: concordance, discordance, and why. Clinical pharmacology & therapeutics 2020;107(1):195–202.

[21] Faden LB, Kaitin KI. Assessing the performance of the EMEA’s centralised procedure: a comparative analysis with the US FDA. Drug Information Journal 2008;42:45–56

[22] EMA. EMA/471951/2016. Conditional marketing authorisation: report on ten years of experience at the European Medicines Agency. 2017. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/ en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation/conditionalmarketing-authorisation (accessed 22 June 2020).

[23] Beaver JA, Howie LJ, Pelosof L et al. A 25-Year experience of US Food and Drug Administration accelerated approval of malignant hematology and oncology drugs and biologics –a review. AMA Oncology e 2018;4(6):849–856.

[24] Olsen K. US FDA accelerated approval (AA) withdrawals. DIA Abstract 2020.