Within this continuing professional development (CPD) article we introduce some practical models and tools that can be actively utilised to the benefit of any manager who is responsible for implementing change.

An effective change plan is an integration of hard and soft systems. Hard systems are the traditional planning tools and techniques (eg, work breakdown structures, Gantt charts [a type of bar chart that illustrates a project schedule]). Soft systems are the psychology and peopleoriented processes designed to maximise engagement. Where the hard systems are tangible, measurable and controllable, the soft systems can be more emotional and intangible. Table 1 compares the soft and hard systems approach to give the reader an idea of actions and associated timings, and how the two systems should run concurrently. The soft systems approach is based on sources of Senior[1] (2002) and Kotter[2] (2007). The hard systems approach is an overview of a standard approach to project management.

Change is more than a process

When managers attempt to “project manage” their way through change, without consideration for the soft systems, they frequently face a backlash of team resistance and disengagement. An effective change management programme requires a step-by-step process to achieve a specific outcome. However, the difficult part of change is not usually the hard systems (the strategies and plans), instead, it is the soft systems, ie, the engagement of people.

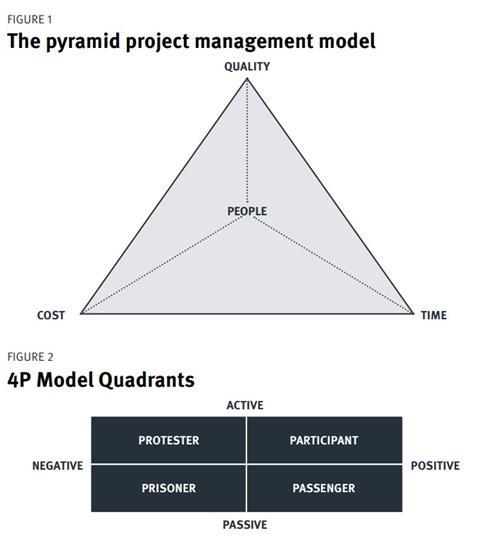

The “time-cost-quality” triangle is a classic project management model of three interlinked components. If you change one element, it will affect the other two in some way. It might also be argued that you can have two of the components but not three. For example, if you want to cut cost, it is likely to have an impact on quality or time, or if you want high quality, it will usually take longer or come at a higher cost.

Although it is not a cure-all solution, envisage a pyramid (Figure 1) and place people at the pinnacle. Consider the impact on time, cost and quality when people are not engaged in a task or activity. Further, consider the impact if they are actively resistant. When staff are not engaged, time, cost and particularly quality are likely to suffer. From a manager’s perspective, it is certainly worth investing energy into getting their team on board and then keeping them on board. This, in turn, will help to make a change programme more effective, while meeting deadlines and remaining within budget.

John Kotter[2] suggests that, in organisational change, we need 75% of management on board in order for the change to be effective. This can be applied to the lower team level. By engaging 75% of the team, the change will gain a momentum and, indeed, the greater the “on-board” percentage (above 75%), the smoother the transition.

| Soft systems | Hard systems |

|---|---|

|

Diagnose current situation (present state) and develop vision for change (future state):

|

Initiate/define (what and why):

|

|

Develop an action plan:

|

Plan (how):

|

|

Implement change:

|

Implement (do):

|

|

Assess and reinforce change:

|

Closure/review:

|

Managing the people

Henceforth, we focus on the soft systems, ie, how to prepare for change by understanding the psychology of people, how to engage the people and how to maintain motivation and momentum throughout the change programme.

Psychological reactions to change

Managers must anticipate the potential push-back they might encounter from their team when implementing change. Unexpected dissatisfaction can become tough to manage, both in terms of time and emotional energy. Depending on the nature of a change programme, people’s initial reactions may range from agreeable acceptance to radical resistance. In terms of a psychological seesaw, with resistance on one side and motivation on the other, if the resistance to change outweighs the motivation, then the change will either fail or will not be sustained. If there is enough motivation, the change programme will be accepted and will gain momentum. Motivation must therefore outweigh resistance for change to gather momentum.

Resistance can come from different places, including senior management, the team and from the manager themselves. No matter how positive a change is, there is also likely to be loss of something. Resistance is often caused by individuals losing (or fearing losing) one or more things from their “psychological contract”, ie, the list of things that are important to them about their job or workplace (see Case Study: The psychological contract and the hierarchy of criteria).

People often do not resist the change itself, but they do resist being changed. Most people like to feel they have some sense of control and choice over themselves and their destiny. In a similar fashion, people might resist the content of the change (ie, the “what”) or they might resist the process (ie, the “how”).

When managers are required to manage their team through change, they would benefit from asking themselves the following resistance questions about their team and the individuals therein:

- What might they lose if they get on board?

- What might they gain if they do not get on board?

- What might it cost them to get on board?

- What might they fear about the change?

With a list of potential resistance, the first step is to identify any of the resistors that can be overcome or removed. For example, if “don’t understand” is a resistor, we can potentially remove that through providing clear information.

Subsequently questions should be asked in order to develop some ideas for motivation to counterbalance or weigh off against the resistance.

- What might they gain if they get on board?

- What might they lose if they don’t get on board?

- What might it cost them to not get on board?

- What might they find attractive about the change?

A final approach to handling potential resistance is called “utilisation”, whereby there has been no such thing as resistance, but simply attraction to an alternative:

- What alternative are they attracted to?

- What do they gain from that alternative?

- How might you meet those gains in other ways?

Engaging the team

The fundamental approach to engaging the team is involvement. However, the degree of involvement is dependent on:

- Impact of the change How market-sensitive is the change? Does the team understand the implications of their own decisions, actions and communicationsin relationship to the change? If the impact of an organisational change is significant, involving the staff too early could mean an increased risk to the organisation

- Level of understanding What level of knowledge and understanding does the team have about the change? If the team is inexperienced or does not understand the context of the change, it would be foolhardy to ask team members to input

- Flexibility of process How much flexibility is there in the change process? How much room is there for negotiation? If the process is already decided, it could be detrimental to ask for input that cannot be utilised. People often see this as “lip service”.

The manager should focus on the events and activities that the team can get involved in. Often during a change programme, the outcome is set (ie, the change is going to happen) but the process is flexible (ie, how we deliver this is up to us). Even if the outcome and process are fixed, the team will still have to manage the effect the change may have on it and its workload.

A number of points can assist with engaging the team. When you, as the manager, are briefed about the change, ask questions that you know your team will ask you. Go into your own team briefing as prepared as possible. Furthermore, when briefing your team, make sure you provide the background and need for the change (eg, is there a problem that the change is solving?). This helps to create a sense of urgency. Then tell the team the desired outcome and vision of the change. Ask for ideas and input – for example, how the change programme might be delivered. If required, create a focus group to get input from those who will be applying or most affected by the change.

Finally, consider some “change champions”. The best champions are those who are the influencers in the team, namely those who can affect the mood and morale of others. It is helpful to have at least one person who is already supportive and perhaps someone who is known to be generally negative and vocal. If you can get the “protester” on board, others will usually follow.

While implementing the change, it is possible for individuals to engage, disengage and re-engage with the change process. This may be dependent on how well the change is progressing and how well the individuals feel they are being treated. The 4P Model[3] defines an arena in which people can move around, based on how active or passive they are being with regard to the implementation of the change and also how positive or negative they feel about the change at any given time. This gives us four quadrants in the arena (see Figure 2).

As a manager, this model can help to identify if individual team members have become disengaged. The aim is to retain at least 75% of the team in the “participant” box, ie, positive and active in implementing their part of the change. Exploration of this model can provide some practical ideas to keep the team engaged or how to re-engage them if they are unhappy or not delivering. For each of the quadrants, we will outline why they may be in this area and then what they need from the manager.

Participants

Participants are on board and driving change. They can see the reason behind the change and the benefits of making it a success. They feel valued and rewarded in delivering what is required and in adapting their approach to suit the new ways of doing things. In terms of what they need from the manager, this partly depends on their personality. Some people will want more praise and communication, while others may require an occasional “thank you”. In general terms, however, participants require acknowledgement for their input, particularly if they go above and beyond. They also need to be updated, involved and reminded of how their actions are contributing to the overall success of the change.

Protesters

Protesters are active but they are not positive. They may not see the point or benefit of the change or they may think the change is not happening how it should be. They may only see the negative side of the change, ie, the losses but not the gains. Protesters need to feel listened to and their points acknowledged. They need to understand the full reason as to why the change is happening and the benefits of making it a success. Take time to listen to protesters on a one-to-one basis; hear their concerns and the driver. If possible, seek to address their concerns or ask them what can be done to resolve the concerns while continuing to deliver on the change.

Passengers

Passengers are on board but they are not driving anything. This may be because they do not really understand what is expected of them, or how to deliver, or the degree of priority compared with their day job. They may be waiting for direction or instruction or busy working on something else. Passengers need a clear briefing on what is expected of them. They need to know how to implement the change so they can get on with it. If necessary, they may need some help with prioritising and diary management.

Prisoners

Prisoners do not want to be on board. They may feel trapped and that the change was foisted on them. They may be experiencing a sense of resentment and lack of control. It is also possible they feel belittled, as if they and their opinions do not matter. At worst, the prisoner may become a saboteur, causing damage to the organisation or its reputation. Prisoners need to be given a channel of communication with the manager, a one-toone opportunity to express their anger or concerns. They need to feel a sense of choice and control. If warranted, be prepared to give them an apology, and hence make them feel as if they and their opinions matter. They may also need a carefully executed escape route, out of the team, the project or perhaps the organisation.

Conclusion

Effectively managing teams through change requires some understanding of the human psyche and personal drivers. It also requires a degree of focus on the psychology of engagement. People are not solely rational, logical beings, but are emotional, too.

[1] B Senior. ‘Organisational change.’ 2nd edition. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall; 2002.

[2] J Kotter. ‘Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail.’ Harvard Business Review, 2007. Available at: https:// wdhb.org.nz/contented/clientfiles/whanganui-districthealth-board/files/rttc_leading-change-by-j-kotterharvard-business-review.pdf (accessed 5 April 2019).

[3] J Hay. Concept introduced in an Organisational Transaction Analysis (TA) workshop. 1999. More information at: www. pifcic.org/intro-to-ta.html (accessed 5 April 2019).